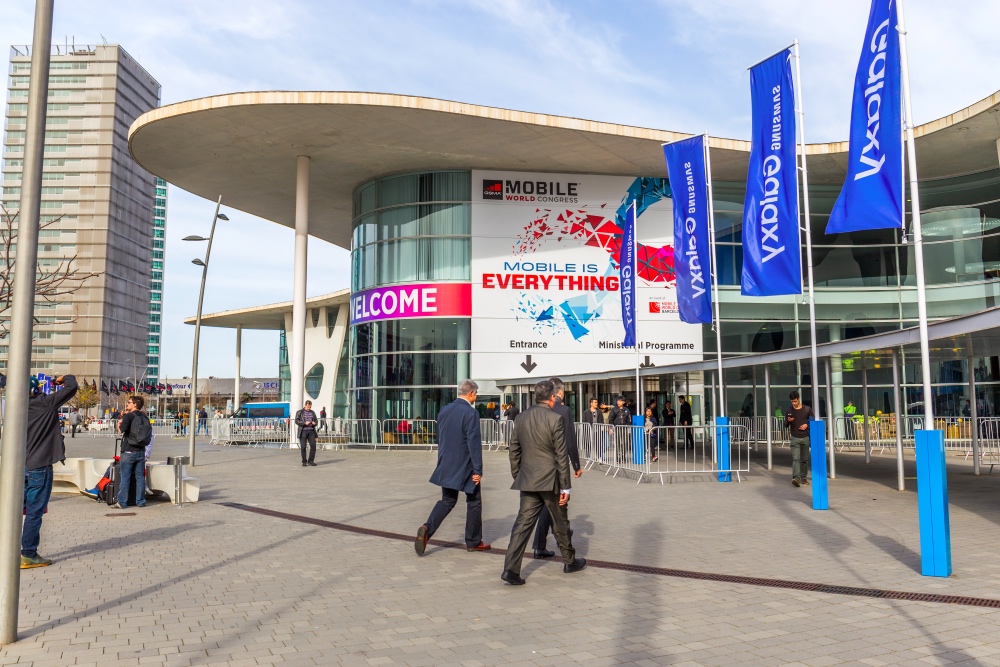

Mobile World Congress (MWC), originally known as the GSM World Congress when it held its inaugural event in Cannes back in 1987, is the preeminent “everything mobile” conference featuring prominent mobile operators, device manufacturers, technology providers, vendors, and content owners from across the world. Now based in the Fira Gran Via in Barcelona, it is a chance for anyone in the mobile industry to meet, negotiate deals, and announce new products.

MWC is held in the last week of February, about a month after the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). While CES is arguably the bigger technology show, where everything from televisions to game consoles are showcased, MWC is the prime destination for “the new mobile” – from smarter phones to IoT to autonomous 6G enabled transportation.

However, as computing, and connectivity become more ubiquitous, there is a thematic convergence occurring between the two shows.

From Bandwidth Enablement to Connected Everything

MWC originally focused around bandwidth enablement, particularly for the Global System for Mobile communications (GSM) standard. While each country would still have its own operators, GSM allowed mobile users to seamlessly travel between countries, use their respective networks and be retroactively billed back, a phenomenon now known as international data roaming. The development of GSM has created a world economy associated with the enablement of being able to travel anywhere, putting the mobile in mobile phone.

Jerome Nadel, the Chief Marketing Officer at Rambus, first attended MWC during its 2002 show at the Palais Congres in Cannes when he was running marketing at Gemplus (now known as Gemalto). That year, Gemplus introduced and trialed 3G SIM cards for the South Korea/Japan World Cup. The 3G trial allowed fans to watch World Cup games via video on demand and check football scores from their mobile handsets.

While on-demand access to real-time scores in a football game is a feature that is taken for granted in the present day, such a notion was arguably beyond the wildest imaginations of most people in 2002. Sports fans would no longer require access to a computer, much less a television, to keep track of their favorite team’s performance.

Nadel argues that while MWC initially focused on the capabilities of mobile technology, the show has shifted towards human experience. Over time, bandwidth has developed to the point where data downloads and transfers are seamless, and phones became more powerful with larger, more accommodating screens. These developments, expressed poignantly at each MWC, brought fixed line computing into everyone’s hand, signaling the beginning of the mobile computing revolution.

That revolution naturally led to everything being connected. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007, while not the first smartphone, redefined the mobile industry and its parameters. People around the world would have instant access to real time information, developments, and to each other. One example is the Arab Spring of 2011, where protestors coordinated through Twitter and Facebook to organize rallies against their governments, with people around the world following the events closely as they developed. With the arrival of more powerful mobile devices that aggregate and curate consumable content, the shift has increasingly moved towards a world where everything is connected. Industry leaders are widening their scope over what can be connected, such as smart cities, smart ticketing, and autonomous vehicles.

All Roads Lead to Connected Everything: Connecting CES and MWC

Since the advent of mobile devices and connected services, there has similarly been a shift from consumer electronics to connectivity for CES. It is becoming increasingly difficult to talk about consumer electronics and mobile devices without also talking ubiquitous connectivity.

The most recent CES show has showcased products such as Razer’s shell accessory that converts their phone to a laptop, mirrors that analyze the user’s skin and organizes their wardrobe, and Optima’s 4K projector that responds to Alexa voice commands. Similarly, past Mobile World Congress shows have featured a digital carry-on suitcase that is trackable and opened through a mobile app, a ground-based drone that can carry up to 20 pounds of food for home delivery, and ZTE’s smart air conditioner that links with the user’s phone and smart home. Things have gotten to a point where both shows are beginning to showcase very similar, if not the same, products and concepts.

Image Credit: All Home Robotics

“Where CES began to tout consumer electronics from toasters to consoles, it is now a venue for connected everything,” Nadel says. He notes that MWC, while it started with a different focus, is nevertheless converging with CES, having “began its evolution focused on technology that has moved from networks to handsets to content to experience to connected everything.”

Connected Convergence

MWC occurs around a month after CES. While some might argue that CES is a bigger show, owing to its broader, more general focus on consumer electronics, the proliferation of connected everything has led to a convergence between the two shows. MWC’s track record of promoting bandwidth and hardware powerful enough to bring the power of connecting to everything to the palm of one’s hand, has brought a great amount of focus on connected everything, not just on smartphones, but autonomous cars, smart cities, and any Internet of Things (IoT) device.

Similarly, for CES, consumer electronics have become so sophisticated and powerful that it is impossible to speak of them without also speaking of their potential for connectivity. Connected everything is the point of convergence for the two shows.

Nadel is optimistic about the future of MWC, and by extension, the development of a more connected world.

“We live in a ubiquitously digitized connected world, where everything is more and more connected. Welcome to MWC 2018.”